Pain

The suffering Pilgrim: pain, the body and love.

On the final 200 kms of the Camino the number of pilgrims doubles, then triples. I am always impressed at the determination with which those who have newly joined the Camino battle on, hobbling, limping and being left behind by their friends. The first few days frequently bring blisters, pulled muscles and strained tendons to pilgrims. On the rest of the Camino I would meet individuals with physical injuries but on this last stretch the cripples form a crowd. Many wear T-shirts proclaiming, “No pain, no gain”.

Few have to abandon the pilgrimage and then only out of extreme necessity. The Camino is no ordinary hike. Those who walk it seem to have an energy, a drive and an engagement with their Camino which accepts physical pain as part of the journey. Certainly, part of this determination comes from accepting the challenge of pushing our bodies a bit more than our normal comfort limits. That is always satisfying. However, it can be very much more than this.

Most of us are aware of our own inner pain: an awareness which sharpens when we are walking day after day. Many of our usual escape routes are closed on Camino: television, internet, parties and drugs. Even if we manage to put these in our rucksacks, we still have to put in the kilometres on foot. There is a very close relationship between emotional pain and physical pain, between blisters and grief, sprains and discontent with our lives, toothache and feeling trapped. As we take each step, body, mind and soul gradually come together in the one that they always have been. On the long caminos this process can go the whole way to experiencing complete union with everyone and with everything and with God. I don’t believe that this is unusual. Many fellow pilgrims have spoken to me of this, or written about it.

Our sense of the spiritual and the physical is heightened on the Camino. Our spiritual self is only as far away as we want to keep it and in places it spills over into the consciousness of many. It may surface in a simple, “Buen Camino”, or when someone offers to take a photo of you with your own camera, or a special moment of liberation at the Iron Cross, or you let everything pour out of you in tears, to a pilgrim you have only just met. This is without mentioning the moments of deep silence and immersion in nature. Our bodies, too, are not easy to ignore on the camino. This is especially so when we are in pain.

Penance: the sacred practice of self-inflicted physical pain.

Pilgrimages have always been made for many motives but traditionally they all shared an element of penance – hence the indulgences associated with them. Christians used to deliberately hurt themselves physically. Until the 1960’s, most religious orders still commended the practise of wearing of spikey chains on the arms or thighs, or rough inner garments or self-flagellation with chord whips. We can easily confuse this, today, with ideas of self harm, but the intention was quite the opposite. The idea was to show sorrow for sin. Overall it is easy to become confused by the logic of it all. I was taught it was something to do with Jesus dying for my sins on the cross.

[mapsmarker marker=”17″]

My puzzlement at the Passion of Christ.

For most of my life I couldn’t make any sense of why Jesus had to die in such a painful way. The explanation that he died for my sins and for everyone else’s sins seemed exceedingly far-fetched. I also had trouble seeing any reason why I should cause my body pain. Overall, this part of the Christian Good News seemed morbid, possibly a bit deviant. If I had done something wrong and was caught I wanted to suffer as little as possible, not add to the inconvenience of being found out.

Samos: Albergue and Monastery.

The albergue in Samos is part of the monastery and is run by volunteers from the Amigos de Santiago. In the evening pilgrims can take part in vespers, the penultimate office of the day. It is usually fairly full. Many comment afterwards on the quality of the singing which is pretty awful and on the age of the monks which is, on average, about 75, although I hear that they now have postulants and a novice.

The monastery has a long history dating from the time of the Visigoths. I have been told, although I can’t find evidence for it, that the foundation began when a small group of hermits, believing the site was a perfect place to install their cells, murdered all the local inhabitants who were heretics. (They were Arians: Christians who didn’t believe that Jesus was God.) The monastery has not had a peaceful history being destroyed on several occasions since. Perhaps its origins still cry out for justice. The church has, for me, a creepiness to it which is not helped by a statue of an armoured knight with one foot on a severed head.

Mass in Samos.

I first passed through Samos on the third Sunday after Easter, 2010. There was a mid-day Mass about to begin, so I went into the Church and looked at the statues and grave stones of famous people, then waited for Mass. The singing had no life in it and I felt sad to see the community apparently on its last legs. I can’t remember the sermon but that is probably because of what happened afterwards.

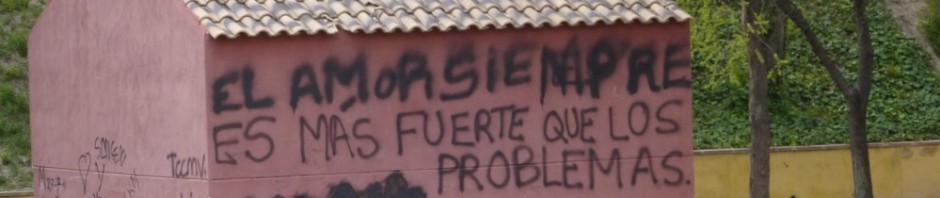

At some time during the Mass, I found myself looking down from the Cross with Jesus wholly aware of a Love which overcame all the pain. The pain was nothing compared with this love for everyone around, the soldiers, his disciples and those who laughed at Him. Nothing could prevent this Love from veiling with peace the violence and terror of the murder. It forgave the abuse of the onlookers and his own people who had condemned him and had him tortured. The basic rottenness within us is transformed by this Love. “Father forgive them, they don’t know what they are doing.” Love is what always survives, in this Love there is no fear and no other desire but to remain within it.

I find it hard to put this experience into words but my pains became insignificant when I experienced this Love, rather like John says in his gospel about the joy of a woman who has gone through labour when she holds her baby. (John 16.21)

Letting Pain transform us.

I don’t see why any of us should seek out pain. It is an intrinsic part of life. Especially as we age we live with more and more physical pain. We also cause pain. It is a given. On the Camino it is something, usually minor, which is dwarfed by the overall joy of the Camino. In everyday life, too, pain can be dwarfed by love. There is another mysterious effect in which pain is not just dwarfed but actually transforms who we are. This happens, I think, through compassion. What happened to me during the Mass in Samos was that I felt compassion – one with the Passion. Everything we do with love increases compassion. Compassion marries my suffering to all suffering, to all humanity, in Love.

There are many techniques for dealing with pain, focussing on the pain, or standing outside of our bodies and seeing the pain within us, symbolising it, not identifying with it, ignoring it and so on. Christians have another option. I feel I can now take my pains and join them with Christ’s Passion. I can be Passionate, compassionate, part of the passion of all men and women. I bathe in Love.

I realise now that I am saying things which I have heard others say before but just not “seen”, or experienced. “My weaknesses become my strength”, says Paul somewhere. What once made no sense, I now feel within my bones.

The Camino may bring pain which we can endure all the way to Santiago. Our bodies can become sacredly present to us. For the first time at Samos I knew that the Camino was telling me something new about my pains. They are not simply to be endured: they are part of my prayer in which I can get nearer to God within me and allow me to see the goodness in everyone else, even if they get the last bed at the hostal just before I arrive (because their taxi was quicker than my aching legs.)